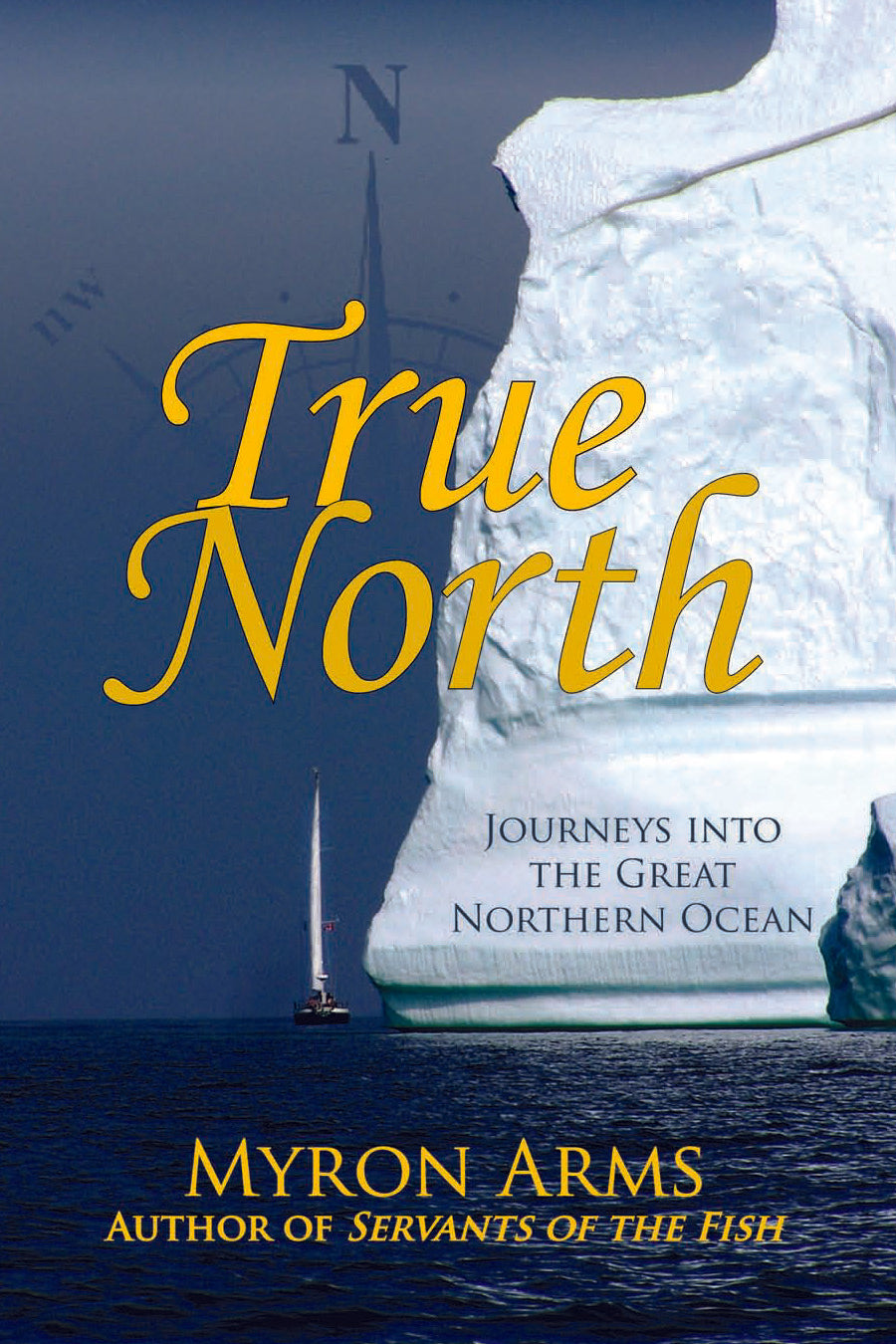

From the fiords of northern Labrador to the ice fields of western Greenland, from the outports of Newfoundland to the tiny fishing villages of Iceland and the Faroe Isles, bestselling author and lifelong sailor Myron Arms chronicles the experience of two-and-a-half decades of voyaging into some of the most remote destinations on Earth.

Presented as a series of sixteen personal essays, True North is at once a tale of white-knuckled adventure, a celebration of natural places, and a quest for contact with the planet we live on. The first five essays explore the motives of the author and those who sail with him on their first forays into the summer Atlantic. The next six essays evoke the allure of northern landscapes—the challenges of a stormy night at sea, the uncanny light of the Arctic sun at midnight, the pathos of pilot whales being driven to slaughter. The final five essays explore the geology, the archeology, the biochemistry, and the natural history of these same northern landscapes, broadening and universalizing their meaning until they become windows into the complex workings of the planet itself.

Thought-provoking and environmentally savvy, True North expresses one man’s fierce determination “to encounter the natural world, to live deliberately within it, to strive to minimize one’s footprint upon it, and to bear witness to it before it is altered irretrievably—before it is lost.”

Educated with graduate degrees at both Yale and Harvard, Myron Arms is a writer, lecturer, and professional small-boat sailor. He is author of several books, including Boston Globe bestseller Riddle of the Ice, and has published more than fifty feature articles in Cruising World, Sail, Blue Water Sailing, and many other sailing and adventure magazines.

A US Coast Guard-licensed Ocean Master since 1977, he and his wife, Kay, have now voyaged over 130,000 sea miles, including two high-latitude crossings of the North Atlantic, a voyage to western Greenland, and eight summer sail-training voyages to the coasts of Newfoundland and Labrador.

As this book went to press, he began his ninth journey to northern Newfoundland with a group of new sail trainees. Readers may sample his other writing and may follow this and other sailing adventures on the web at www.myronarms.com.

Content

Part I Setting Out for Ithanka

1. Shakedown

2. Landfall Faroe Isles

3. Searching for the Edges

4. The Wreck of the Braer

5. Seeking Experienced Crew

Part II A Gaunt Waste in Thule

6. Waters of Separation

7. Gale Warning

8. Northern Light

9. The Passing of Whales

10. Footprints

11. A Gaunt Waste in Thule

Part III Time and the Rock

12. Messages in the Earth

13. Ancestors

14. Milk Sea

15. A Dune Adrift in the Atlantic

16. The Beneficent Gene

Notes

Bibliography and Further Reading

Personal Acknowledgments

About the Author

"Veteran sailor Arms (Servants of the Fish) writes a notable collection of essays of the sea and sailing in the far reaches of the Great Northern Ocean, braving the frigid waters and dodging the dangerous ice fields. His trusty boat, Brendan’s Isle, and his sturdy crew, which includes his youngest son, Steve, move through these cold crossings with few perilous incidents, maintaining watch and the standard sea responsibilities. Arms’s narrative is rich, descriptive, almost poetic, and full of voyaging on the water as he journeys along the fiords of northern Labrador to western Greenland and among the fishing villages of the Faroe Isles. Much more than a slight travelogue, the book hits its stride when Arms cautions against 'expanding human waste, changing atmosphere chemistry, disappearing species, rising sea surface temperatures, thinning sea ice, and melting glaciers.' (Jan.)

"After lifelong sailor Myron Arms finished building his 50-ft cutter, he set off to the northern seas in search of adventure. Over the next two and a half decades he found isolated cultures, new companions, harsh weather and an enchanting pilgrimage that took him on the route of an ancient Irish warrior, Saint Brendan. Written as a series of 16 personal esseays, True North will leave you entranced with its tales of ice, mystery and hardship on some of the world’s most challenging waters."

"True North is the latest in the slight but remarkable oeuvre of Myron Arms. Teacher, sailor, explorer, writer, his previous work includes Riddle of the Ice (1998), Cathedral of the World (2000), and Servants of the Fish (2004). I am embarrassed to admit that I have read none of these books. Considering the length and breadth of my reading on marine subjects, how they escaped me is a mystery. However, if you are in my regrettable state, True North is a perfect introduction to Arms’ work . . .

The ambitious itinerary gives you an indication of the breadth of Arms’ preferred cruising grounds as well as his curiosity. But he wasn’t just cruising and he wasn’t just curious. A high school teacher in the 1970s, he traded in the classroom for his first blue water boat and founded (and led) a program of 'sea learning' experiences. As a licensed Coast Guard ocean master, he sailed with hundreds of teenagers for the next five years. While aboard, they conducted a variety of scientific experiments. 'The teacher was the sea…It was the beginning, really, of my own emerging awareness of the stresses being suffered by virtually all of the world’s marine environments.'"

"As the essays follow the journeys of Brendan’s Isle over the years, scientific information and analysis becomes more of a narrative focus than the more simple pleasures of the beauty of the physical world and the exhilaration of sailing. With this focus, the text becomes more engrossing, the journey more unique and urgent and ages of the crews grow up–from high-school-ers to young adult 'sail-trainees.' What they discover over the course of more than twenty years is that in an environment that at first seems huge, fierce and implacable is as vulnerable as an alpine flower.

The northern seas were never meant to be lived upon by humanity, but that never stops some people. True North: Journeys Into the Great Northern Ocean tells the story of life in the northern seas from Myron Arms as he reflects on his times in the northern Atlantic through essays on his adventures. A new perspective on ocean life and the arctic circle, True North is an entertaining and intriguing read that should not be ignored."

"Veteran sailor Arms delivers a richly descriptive, almost poetic collection of essays about sailing up and down fiords from northern Labrador to western Greenland and among the fishing villages of the Faroe Isles. The sturdy crew of his trusty boat, Brendan’s Isle, included his youngest son, Steve."

From the Introduction to True North

Perfect Travelers

Imagine a moment in the Northern Ocean one morning fourteen centuries ago, in a time when the Earth had not yet been ravaged by humankind: The surface of the water rises and falls in a lazy swell under a featureless gray sky. There is no sound of wind. The sun appears as a dim halo of light obscured behind ribbons of stratus cloud. Seabirds wheel and dive over a series of concentric rings in the water where a pair of whales has just sounded. Near the rings, shrouded in a veil of mist, moves a tiny ship, forty feet long and ten feet wide, fashioned out of animal skins and wood.

From a short distance away the ship looks like the discarded shoe of some gigantic walker of the Earth, covered as it is with rectangular slabs of blackened ox hide and sewn together with heavy thongs of horsehair, flax, and tallow. Brown flaxen sails are lashed to yardarms atop the two wooden masts, each sail painted with red ochre in the form of a Celtic cross. At the masthead above the larger of the sails, a long silken pennant hangs limp in the stagnant air.

A company of fifteen men lives in this ship. Several stand together this morning in the uncovered center section of the vessel, two facing forward on either side of the steering oar, four others facing aft and pulling together on a pair of long wooden sweeps. The remainder of the company rests in the ship’s dank bowels where they endure the semi-darkness and the high animal odor of a place where too many men have lived and eaten and slept in uncomfortable proximity for too long.

The voyage these men have made is nearly six weeks old, although most of them have forgotten this fact by now. The continual parade of nights and days of wandering across ice-strewn seas has caused the measure of time to grow indistinct. Hours have passed into days and days have passed into weeks until there is no longer any certain means of counting the time. The men have sailed their ship to the accompaniment of rain and sleet and summer gales until it seems they will never see the land again . . . until this moment . . . this long awaited, terrifying moment.

Suddenly somewhere beyond the curtain of fog come the sounds of an unknown coast—the faint chatter of seals, the cry of gulls, the grinding of surf against a granite shore—sounds that stop the breath of every man aboard the ship. The dangers these sailors have faced for so long, dangers of storm and cold, hunger and fatigue, seem in this moment almost benign as they are replaced by the even more uncertain dangers of the land.

The leader of the company moves aft to take over the steering oar. He exhorts his shipmates to gather their resolve and to arm their spirits with hope. He utters a prayer of thanksgiving to the Christian God whom he is certain has brought them to this landfall, and he points the leather ship in the direction of the sound, urging his oarsmen onward.

The loom of a rockbound headland materializes slowly out of the mist as the helmsman maneuvers the leather ship into the mouth of a large bay. In another few minutes the air clears completely, revealing “a wide land, rich in fruit and flowers and autumnal trees.” The helmsman propels the vessel deep into the bay until it is engulfed by the sweeping shoreline. Here he makes one final pull on the steering oar, driving the prow of the ship onto a beach of golden sand. He climbs to the gunwale, steps out onto the shore, and falls to his knees in prayer.

When he rises to his feet again, he surveys the shoreline and the lush forests beyond with a slow sweep of his eyes. Surely, he thinks, this is the land that has filled his imagination for so long—the land that Barrind described to him, the place Saint Mernoc visited so many times. Surely this is the green and fruitful glade that holy men and poets have for generations called the Promised Land, the “Blessed Isle of the Saints.”

In this manner, on an anonymous summer morning in the sixth century of the Christian era, the Irish sailor-saint, Brendan of Kerry, is said to have achieved the object of his quest: landfall on the lush and elusive island referred to ever since as Saint Brendan’s Isle. The tale of this voyage is recounted in the pages of a Latin text, written down several hundred years later and known throughout medieval Europe as the Navigatio Sancti Brendani. The story was widely popular during medieval times, attested to by the fact that more than a hundred hand-copied manuscripts still survive.

The tale continues in the words of the Latin text:

[Brendan and] the monks disembarked . . . [and] when they had gone in a circle around land, it was still light. They ate fruit and drank water, and in forty days’ exploring did not come to the end of the land.

The text concludes with reports of further exploration, with the discovery of a “great river” that divides the land, and with an encounter with a holy man who speaks to Brendan in his own language. This man cautions Brendan to return without delay to his home in western Ireland and foretells of the sailor’s approaching death. In a few more paragraphs the story ends. Brendan sails home and dies soon afterwards among his friends and disciples, but not before he is able to describe to them—and eventually to the world—all the wonders he has witnessed.

Ever since the writing down of the Navigatio more than a thousand years ago, the question has remained: Was Brendan’s journey to the mysterious island a real voyage? And is the place that he is said to have discovered a real place? Archeologists and explorers, geographers and historians have argued about this question for generations. Cartographers during the first few centuries of the Age of European Discovery drew imaginary locations for Brendan’s Isle in every corner of the North Atlantic Ocean. On some of the maps it was located where the Azores are now known to be. On others it appeared near Bermuda, Iceland, or Newfoundland. But on most of the early maps, it was simply drawn as a mysterious terra incognita, a land shrouded in fog somewhere out in the trackless waste of the northern ocean, surrounded by strange sea creatures and monsters of the deep.

In our own times there has been renewed interest in confirming (or debunking) the historical veracity of the voyages of Saint Brendan. In the late 1970s an intrepid young historian, Tim Severin, actually built a replica of Brendan’s leather curragh and sailed it from County Kerry in western Ireland to the Atlantic coast of Newfoundland in an attempt to prove the feasibility of such an undertaking. The story of his two-year odyssey was chronicled in a book, The Brendan Voyage, and later also appeared as a featured photo-essay in National Geographic. Yet even as Severin’s modern voyage proved without a doubt that such a journey could be accomplished, it still stopped short of proving that a particular Irish cleric had made an actual historical voyage to a real place somewhere in the wilds of the western Atlantic.

In spite of all attempts to the contrary, it seems that the saga of Brendan and his fourteen “jolly saintes” belongs to the realm of legend—and here, in all probability, it will remain. Perhaps this is as it should be. Perhaps in the end it doesn’t really matter whether there was an actual historical person named Brendan of Kerry who sailed an actual leather ship to the shores of the New World. The most important thing about this intrepid Irish explorer may simply be that we have his story. And his story, whether fact or legend, may be all we need.

The saga of Brendan’s seven-year odyssey is unique in two important ways. Not only does it survive as the earliest written account of European contact with the unknown lands beyond the western ocean, but it also stands alone in the literature of European discovery as a testimony to a special kind of journey—a journey of the imagination and the spirit. Brendan and his crew set out in search of the Blessed Isle without economic motives or self-aggrandizing schemes. Their purpose was not to lay claim to new territories, subjugate native populations, or seek for gold or riches. They weren’t looking for a northwest passage to the Orient. They weren’t planning to trap for furs or establish a summer fishing station. They had, in fact, no other purpose for making their voyage than to witness for themselves the grand and terrible beauty of a wilderness they had heard extolled in legend but had otherwise only vaguely dreamed.

“The themes [of the Navigation],” writes American nature writer Barry Lopez, “are of compassion, wonder, and respect” as opposed to the more familiar themes of bloodshed, plunder, greed, and conquest that typify so much of the history of early European contact with the American continent. Nowhere else in the long chronicle of European discovery is there a tale of another voyage quite like this one.

The Icelandic Sagas of the tenth and eleventh centuries describe several attempts by early Norse explorers to wrest fertile lands from their aboriginal inhabitants and to establish permanent trading colonies of their own on the shores of the New World. Four centuries later, the record of the Columbus voyages echoes many of the same themes and establishes the rule for all who would follow—Cortez and Balboa, Verrazano and Cabot, Frobisher and Cartier—as they set out to plunder the American continent or to discover lucrative trade routes to the wealthy markets of the Far East. Hundreds (eventually thousands) followed in the footsteps of these early explorers, virtually all of them seeking land or power or economic gain.

The Navigation of Saint Brendan, in contrast, is the tale of a voyage with a simpler objective. As Lopez again observes, it is the story of a group of “impeccable, generous, innocent, attentive men [who] were, one must think, the perfect travelers.” Their journey was a pilgrimage of sorts, yet they did not sail as proselytizers or missionaries. Instead, they pursued their quest as celebrators of the Earth and as chroniclers of its awesome majesty. It was enough for these travelers to bring home memories of what they had seen and afterwards to tell the story or their voyage to all who would listen.

* * *

I first learned about the voyages of Saint Brendan more than two decades ago, during a time when I was building a sailboat in my back yard. With my wife Kay and our friend John Griffiths, I worked full time on that boat for almost a year. In the evenings I would read a few pages of Severin’s The Brendan Voyage—that is, when I could stay awake long enough to read anything at all. Then, when daylight came again, I would head back down to the boat for another ten or twelve or fourteen hours of work.

For much of that year the sailboat had no name, although I was too busy at the time to worry about such secondary details. The name would come, I knew, in its own good time. Meanwhile there were more important things to worry about: things such as designing plywood templates for bunks and settees, ordering the next three thousand board feet of Philippine mahogany, cutting out seven hundred cypress plugs on the drill press, gluing up thirty-five cupboard doors, building the icebox and the navigator’s table and the companionway stairs.

I knew what I was hoping to do with this boat once she was finished and launched. I wanted to sail her to the lonely coasts around the rim of the North Atlantic basin. I wanted to explore some of the natural places and see some of the wonders that old Saint Brendan himself may have witnessed during his seven years of wandering about the northern ocean. It therefore came as no surprise when the boat’s name suddenly occurred to me—not as an idea but as an incontrovertible fact, as something that had always been. It came while I was working one morning fitting a piece of cabinetry in the main saloon. I was staring at the plank in my hand, concentrating on the asymmetrical sweep of its grain, preparing to mark with a pencil and compass the line that it would take as it fit against the irregular inner surface of the hull. One moment there was nothing in my mind but the task before me. The next moment there was a name: Brendan’s Isle.

I felt as if I’d just emerged from some kind of temporary amnesia. Surely, I thought, I’d seen this name before. Maybe it had been written on the bill of lading from the shipping company that had delivered the empty hull and deck from the shipyard in Taiwan. Maybe it had been stamped onto the pine crates containing the spars and standing rigging that had come from New Zealand. Or maybe it had always been there, printed on the boat’s transom in some kind of invisible braille, and I had only just now learned how to decipher the shape of the letters.

Brendan’s Isle: the name had a romantic ring to it, a suggestion of faraway lands and olden times. It brought to mind the geography of the northern Atlantic—an apt connotation in light of the plans that were already forming in my mind about the places I wanted to sail. The name also suggested good luck. Saint Brendan, by all reports, had been an unusually lucky sailor. His chroniclers often used the phrase “Brendan luck” when describing the knack he seemed to have for avoiding dangers, weathering storms, surviving crises, finding safe landfalls.

On the more practical side, the name Brendan’s Isle was short and unambiguous. On a radio call it would be quick to say. On a customs declaration it would be easy to spell. People would be able to remember it—unlike so many exotic yacht names that are virtually impossible to read or pronounce.

In short, Brendan’s Isle had all the necessary attributes a sailor seeks when he wishes to name a little ship. The phrase was both beautiful and simple. And it seemed to speak to the particular purpose of the boat I was building. It was a name for the grand and mysterious places my shipmates and I would one day be setting out to find, the questions we would be trying to articulate, perhaps even some of the answers we would be hoping to find.

* * *

By July 1983 the building project was far enough along that we were able to launch and sail Brendan’s Isle for a month, from the Chesapeake Bay to the southern coast of New England and home again, in order to sea test her systems and shake down her rig. The following winter Kay and I worked (without John) for another fifteen hundred hours, completing all the final modifications that the boat would need in order to be ready to take on the North Atlantic Ocean the following spring.

Brendan’s sailing plan for the next two years began with a high-latitude crossing of the North Atlantic, a route that took her out past the Grand Banks of Newfoundland, across “iceberg alley,” close past the southern capes of Greenland and Iceland, and on toward the coasts of northwestern Europe. Her first landfall, some twenty-three days and three thousand nautical miles after leaving the Chesapeake Bay, was in the Faroe Isles, a mountainous archipelago several hundred miles east of Iceland and almost the same distance due north of Scotland. The Faroes were a convenient stopping place for Brendan’s Isle and her crew on this frigid west-to-east crossing of the North Atlantic, just as they may also have been for old Saint Brendan as he made his way out into the wilds of the western ocean while sailing in the opposite direction. If, as Tim Severin argues, the old sailorsaint followed the so-called “stepping stone” route across the North Atlantic, he would almost certainly have visited the Faroes (preceded by landfalls in the western Hebrides of Scotland, and followed by visits to Iceland, southern Greenland, and perhaps also the Atlantic coasts of Labrador or Newfoundland). According to the Navigatio, Brendan and his shipmates made landfalls early in their travels in a pair of hauntingly beautiful places Details of the construction of Brendan’s Isle’s main cabin described variously as the “Isle of Sheep” and the “Paradise of Birds.” Both names strongly suggest the Faroe Isles—as they surely must have appeared a millennium and a half ago and as they still appear today.

I had no conscious intention, as my shipmates and I started off across the Atlantic in the spring of 1984, of following in the footsteps of the old Irish sailor-saint. The legend of Brendan’s voyage was engaging—the idea of a mysterious island somewhere out in the middle of the Atlantic was romantic and exciting. These were reason enough, I felt, for the name that appeared on the transom of our little sailboat. I had no thought as our first summer’s sailing plans evolved of following specific routes that Brendan may have followed or of visiting particular places that he may also have visited.

Yet the morning that Brendan’s Isle sailed up into Hestur Sound, Faroe Isles, and anchored near a place called Brandarsvik (“Brendan’s Creek”), I admit I felt a strange sense of oughtness, as if we had sailed all these three thousand miles just to be in this setting. There was an aura about this place, a ghostlike presence that seemed to bridge the centuries and transform legend into living fact. The ruins of an ancient Christian chapel hunched on the beach, casting the shadows of its crumbling stone revetments on the sand. The dark green hills behind the ruins were dotted with sheep. A thousand feet overhead a thousand seabirds circled in The ruins of an ancient Christian chapel at Brandarsvik, Faroe Isles silence, and for a moment I felt as if I could see the silhouette of a tiny leather ship lying at anchor near the mouth of the creek and the spectral forms of fifteen ragged sailors huddled at the chapel gates, seeking advice from the holy man within about where next to point their bows in their quest for the Blessed Isle.

* * *

Two and a half decades have passed since that day in Brandarsvik—two and a half decades during which I and Brendan’s Isle have voyaged over one hundred thousand sea miles and have visited, in utterly haphazard fashion, virtually every one of the “stepping stones” that the old Irish sailor-saint might arguably have visited during his (equally haphazard) meanderings about the northern ocean. According to the Navigatio, Saint Brendan pursued his quest for seven years, ranging about the Atlantic each summer in a primitive and ungainly vessel whose speed and course were often dictated by the vagaries of wind and weather, and whose ultimate destinations were therefore often left entirely to chance. Each year at the end of their summer’s voyaging, he and his shipmates would seek safe haven to rest themselves and to repair and reprovision their little vessel. Then, the following spring, they would set off once again with a renewed sense of purpose and an ever stronger hope that somehow, this time, they might happen upon the object of their quest.

In contrast, our travels aboard a modern, well-found yacht, efficient in its sail plan and equipped with all the miracles of modern electronic navigation, have been much more predictable. Each of the forays I’ve made into the North Atlantic during the past twenty-five years has been carefully conceived and painstakingly planned. Each has had a cruising agenda; each has had a timetable; each has had a set of predictable destinations. Twice I, with a small crew, have taken Brendan’s Isle from the eastern seaboard of the United States across the top of the Atlantic to Scandinavia, both times calling at the Faroe Isles (and both times visiting the ruins at Brandarsvik).

On the first of these journeys, after a winter layover in southern Denmark, we crossed the North Sea to spend a month exploring the western coast of Scotland, and another month visiting the bays and sounds of southwestern Ireland. On the second, we paused to visit the Westmann Islands, south of Iceland, then to circumnavigate Iceland in its entirety. And both between and after these journeys, we visited the Atlantic coasts of Newfoundland and Labrador on numerous occasions, one of which included a mid-summer crossing of the Labrador Sea and an exploration of western Greenland all the way to the great ice fields of Disko Bay, three hundred miles north of the Arctic Circle.

In the beginning, as I’ve said, I had no conscious intention of following in the footsteps of the old Irish navigator, retracing his voyages, visiting all the strange and marvelous places he might have visited. But fifteen years later, as I began to reflect on the record of my own travels, I realized that Brendan’s Isle and I had in fact been pursuing an unspoken pilgrimage of sorts, stringing together a series of voyages that may have seemed random and disconnected when considered separately, but that began to form a compelling pattern when considered as a whole.

Eventually, by the summer of 1998, I realized there were only a handful of stopping places along the old “stepping stone” route that Brendan’s Isle had not visited, and I set about to rectify the oversight. That summer, during our second circumnavigation of Newfoundland, Kay and I and our shipmates visited the tiny village of Saint Brendan (as good a candidate as any for the actual historical site of Brendan’s New World landfall). Two years later, during our second eastbound trans- Atlantic crossing, we paused to call at the volcanic Westmann Islands, south of Iceland, there to witness the eerie, desert-like nakedness of Surtsey, a recently formed volcanic pinnacle that may be a modern counterpart to Saint Brendan’s “Island of Smiths,” the smoke-belching A view of Brandarsvik from the road above the settlement island in the Navigatio whose inhabitants hurtled hot, molten rocks at the monks as they sailed past.

Finally, two decades and more after we had first made landfall at the ruins at Brandarsvik, I began to feel as if I and all those who had sailed with me were on the cusp of completing a quest that we had been pursuing, consciously or not, for many years. We had sailed for one hundred thousand sea miles around the rim of the northern Atlantic, and now, with our circumnavigation of Iceland, we had managed to assemble a sequence of landfalls that might easily have been made by our legendary predecessor— and thus to have fashioned a modern “Brendan voyage” of our own.

The essays that follow are intended as a chronicle of this voyage—or really this series of voyages—and as a celebration of the natural places that Brendan’s Isle and her crews and I have visited along the way. They are offered, with all humility, in the spirit of those perfect travelers, those “impeccable, generous, innocent, attentive men” who were satisfied simply to experience for themselves all the wonders of the natural world and afterwards to tell the story of their voyage.

There will be no overt political agenda here—with one important caveat. The “pristine wilderness” that Saint Brendan and his shipmates discovered in their travels and that were later described in the pages of the Navigatio no longer exists. Much as we might wish it otherwise, we, as a species, have succeeded beyond our wildest expectations over the past thousand years in taming the wild places, subjugating nature, establishing our imprint upon virtually every square inch of this planet. Some of this imprinting may be relatively harmless and inconsequential—styrofoam coffee cups washing up on the beaches of Antarctica, broken soda-pop bottles disintegrating into sea glass on the ocean floor. But much of it—the vast preponderance of it—is far more onerous. As we, the seven billion, have succeeded in taming the wilderness, we have also begun to alter it, often to the detriment of both the other species who live there and of ourselves.

Of necessity, the essays that follow are therefore set within an inevitable if often unspoken context of expanding human waste-streams, changing atmospheric chemistry, disappearing species, rising sea surface temperatures, thinning sea ice, melting glaciers. These things are. They exist as part of the landscape now—so that to claim to bear witness to the beauty of the natural places without also recognizing these threats to their survival is to fabricate a lie. Much as Rachael Carson did more than fifty years ago, I have also learned that it is no longer possible to celebrate the intricate natural rhythms of “the sea around us” without also becoming aware of the human-induced changes that threaten those rhythms from every side.

* * *

The age of innocence is past. We can no longer roam the Earth as old Saint Brendan may once have done, marveling in childlike wonderment at a pristine and unaltered nature. Instead, if we are honest with ourselves, we now must travel as my shipmates and I have tried to do aboard Brendan’s Isle: aware of the changes that are taking place, deeply appreciative of the beauty that remains, armed with a kind of urgency that moves one at every moment to encounter the natural world, to live deliberately within it, to strive to minimize one’s footprint upon it, and to bear witness to it before it is altered irretrievably—before it is lost.