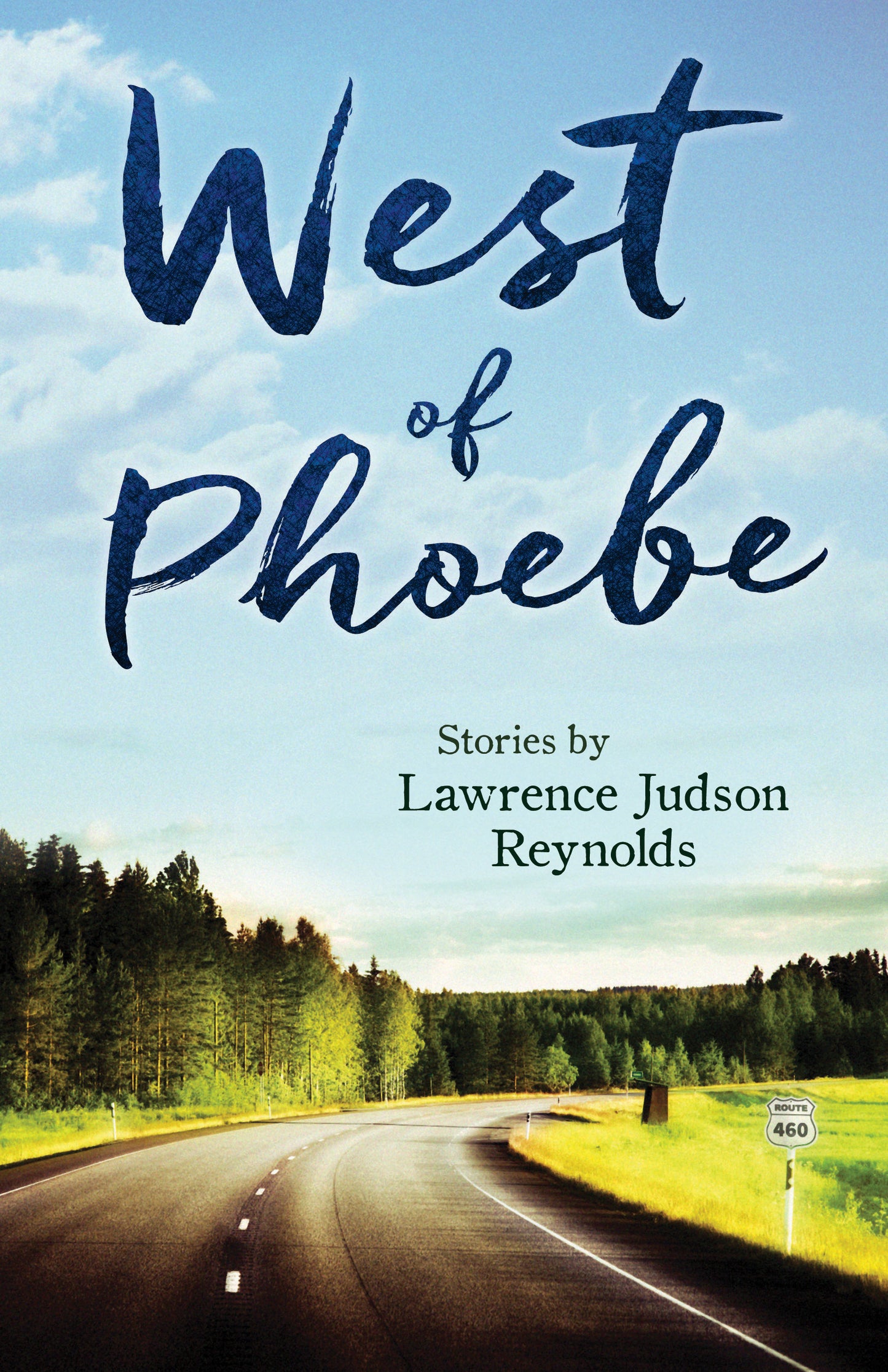

This book consists of eight stories; most of which are loosely connected but no attempt was made to follow a timeline or storyline. They are intended to stand alone as short stories. But, most take place in the mythical village of Phoebe in rural Virginia in the 1940s and 1950s. They are all told from the point of view of one narrator, many when the narrator was a child. Children in this time and place were often left to form their own understandings of events taking place around them in the adult world. The story, “My Father’s Necktie,” is representative of the effect on a young boy of his father’s paralysis from a stroke and the family dynamics that resulted. “A Family Tree” deals with the aftermath of World War II on the members of the Phoebe community. The settings of these stories are mostly intimate and domestic; a country store and old tobacco barn converted to a commercial garage for example. “Early Dylan: Five and Ten Cent Women” is about the narrator as he grows older and breaks away from his early life in Phoebe. All of them together form a dynamic picture of growing up in the old South.

Lawrence Judson Reynolds is from Concord, Virginia. He attended the University of North Carolina at Greensboro writing program in the middle '60s and studied under Peter Taylor. He was a founding editor of the Greensboro Review and has published there and in Cutthroat, Blackbird, Carolina Quarterly, The New Orleans Review, Christopher Street, and Descant. He taught writing workshops at the Virginia Highlands Festival for many years and also taught two semesters of fiction writing at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville. He lives with his wife, Margaret, in Richmond, Virginia.

Contents

Preface by Fred Chappell

Introduction

1. The Man with the Gun

2. A Family Tree

3. My Father’s Necktie

4. Proceedings

5. That Grand Canyon

6. The Half-Life of Holidays

7. Early Dylan: Five and Ten Cent Women

8. Last of the June Apples

About the Author

Preface

The Lonesome Community of Lawrence Reynolds

by Fred Chappell

The eight stories that make up West of Phoebe by Lawrence Reynolds combine to form a portrait of a place and time in our American experience so familiar that they have become strange. It is as if the daily landscape we know so well, each of us separately and together, were presented in the guise of photographs taken with old Kodaks, or even ancient Brownie box cameras. Familiar but strange—sometimes even spooky:

Was the man with the gun actually there? How did the father’s necktie change into a snake and then into the tail of a kite seeking its freedom in infinity? Is the ambiguous relationship of Raymond Miles and Emmitt Kinds, as revealed in “Proceedings,” describable in words, or is its mystery its whole meaning? Is that relationship, of attraction and repulsion simultaneously, analogous to the one between the storeowner and the man who had robbed her fifty years earlier?

None of the mystery that pervades these stories wafts into them from the universe of fantasy. Reynolds presents his narratives in straightforward, nearly deadpan, fashion. Even his confused, daydreaming teenagers report their experiences in closely factual, personally reportorial, manner. They tell us what they see and when they tell us what they feel, omitting no flush of embarrassment, we know that they describe just what they have observed within and about themselves.

All these stories center upon single individuals and sometimes, as in “That Grand Canyon,” upon a single scene. But the characters’ isolated, tightly knit communities are present with them always. Each place they inhabit, the animals they live with, even the inanimate objects they touch possess histories, and none of them, not even outliers like Dalton Dean, in “The Last of the June Apples,” can be separatedfrom the histories. Sherwood Anderson and ThorntonWilder had the ability to draw a collocation of loners into an emotional community. Reynolds shares that talent.

That grand storywriter Peter Taylor once told me in private conversation that Mr. Reynolds’ stories had “quiet power.” When I tried to pursue the subject he purposely drifted from it, as if he too found it difficult to speak precisely about these natural, preternatural fictions.

To salute, as now I do, the fine and unique achievement of Lawrence Reynolds brings me a large and overdue happiness.

Introduction

Route 460 runs through the mythical village of Phoebe. At least it did when I was young, when these stories were first sketched in my imagination. Since then the highway has been moved and a new bypass has taken its place and a piece of history is lost. No matter. History is not really history. You cannot make history from what little we know. You cannot tell the truth with words.

Yet we keep trying. We try to tell the truth about our past. Where we lived. The heartbreak of our love. The cruelty of our master. The whisper of wind through a field of corn. The scorn of people we thought we knew. The depth of our despair. The vastness of our ego. It’s true that I thought I could find the true story of my father, who died when I was nine years old, if I just uncovered every clue, but the truth is large and stretches from here to there with no beginning and no end. The stories in this book are not meant to be true. I hope they carry some truth in them. They are a part of my history.